Sketching Out Magnetism With Electricity

Study Uses an Electric Field to Create Magnetic Properties in Nonmagnetic Material

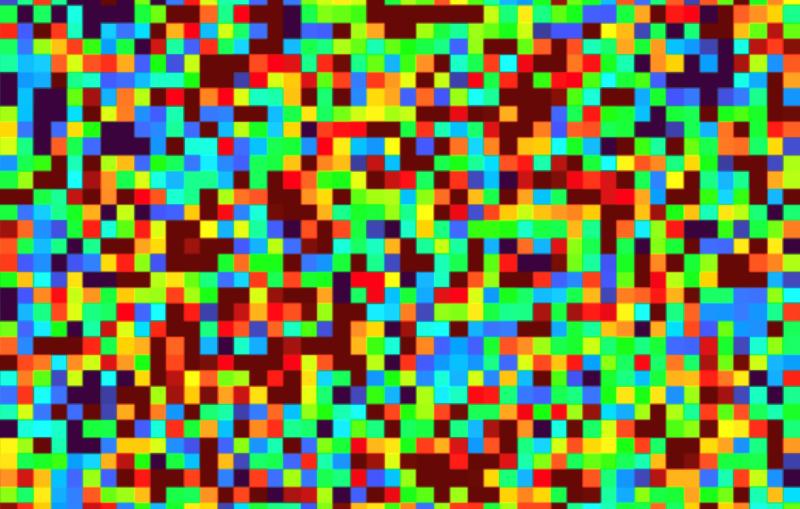

In a proof-of-concept study published in Nature Physics, researchers drew magnetic squares in a nonmagnetic material with an electrified pen and then “read” this magnetic doodle with X-rays.

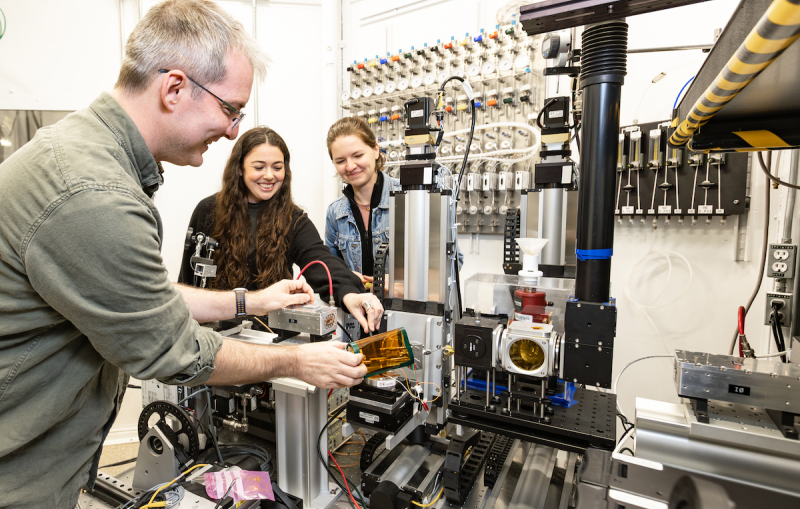

The experiment demonstrated that magnetic properties can be created and annihilated in a nonmagnetic material with precise application of an electric field – something long sought by scientists looking for a better way to store and retrieve information on hard drives and other magnetic memory devices. The research took place at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

“The important thing is that it’s reversible. Changing the voltage of the applied electric field demagnetizes the material again,” said Hendrik Ohldag, a co-author on the paper and scientist at the lab’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

“That means this technique could be used to design new types of memory storage devices with additional layers of information that can be turned on and off with an electric field, rather than the magnetic fields used today,” Ohldag said. “This would allow more targeted control, and would be less likely to cause unwanted effects in surrounding magnetic areas.”

“This experimental finding is important for overcoming the current difficulties in storage applications,” said Jun-Sik Lee, a SLAC staff scientist and one of the leaders of the experiment. “We can now make a definitive statement: This approach can be implemented to design future storage devices.”

Lining Up the Spins

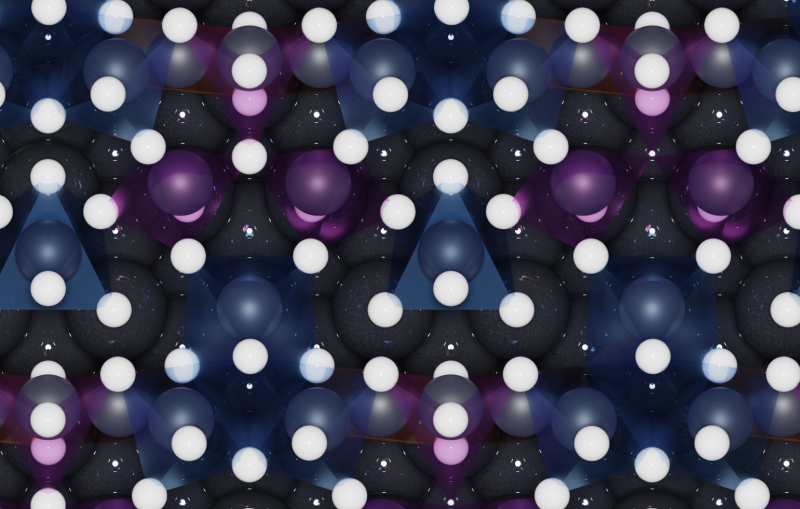

A material’s magnetic properties are determined by the orientation of the electrons’ spins. In ferromagnetic materials, found in hard drives, refrigerator magnets and compass needles, all the electron spins are lined up in the same direction. These spins can be manipulated by applying a magnetic field – flipping them from north to south, for instance, to store information as ones and zeroes.

Scientists have also been trying different ways to create a “multiferroic state,” where magnetism can be manipulated with an electrical field.

“This has become one of the Holy Grails of technology over the past decade,” Ohldag said. “There are studies that have shown aspects of this multiferroic state before. The novelty here is that by designing a particular material, we managed to both create and eliminate magnetism in a controlled fashion on the nanoscale.”

Crosstalk Between Electricity and Magnetism

In this study, the team started with an antiferromagnetic material – one that has small patches of magnetism that cancel each other out, so that overall it doesn’t act like a magnet.

Both antiferromagnets and ferromagnets show magnetic properties only below a certain temperature, and above that temperature they become non-magnetic.

By designing an antiferromagnetic material doped with the element lanthanum, the researchers found they could tune the properties of the material in such a way that electricity and magnetism could influence each other at room temperature. They could then flip the magnetic properties with an electrical field.

To see these changes, they tuned a scanning transmission X-ray microscope at SSRL so it could detect the magnetic spin of the electrons. The X-ray images confirmed that the magnetization had occurred, and was truly reversible.

Next, the research team would like to test other materials, to see if they can find a way to make the effect even more pronounced.

The research team included scientists from the Korea Institute of Materials Science, Pohang University of Science and Technology, Pohang National Accelerator Laboratory, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids and the University of New South Wales of Australia.

Citation: Jang et al., Nature Physics, 03 October 2016 (doi:10.1038/nphys3902)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.